Why Jesus Said “There Is No Such Thing as Sin”

The Gospel of Mary, original goodness, and the spiritual cost of forgetting who you are

“It felt like something I already knew, but didn’t have the words for.”

That was how one woman described the Gospel of Mary after we read it together in a circle of worn-out sofas, tucked in the lounge of a progressive church on a Saturday morning.

When we came across Jesus’s words — “There is no such thing as sin” — the room went silent. Not awkward-silent. Stunned-silent. These were faithful women, many of whom had spent their entire lives in churches where sin was central to the story. And yet no one got up to leave. In fact, they stayed past time, reading aloud, paragraph by paragraph. They wanted to wrestle with it.

That day confirmed something I had long suspected:

This gospel, though fragmentary and strange, is still alive.

“It speaks into the quiet places doctrine can’t reach.”

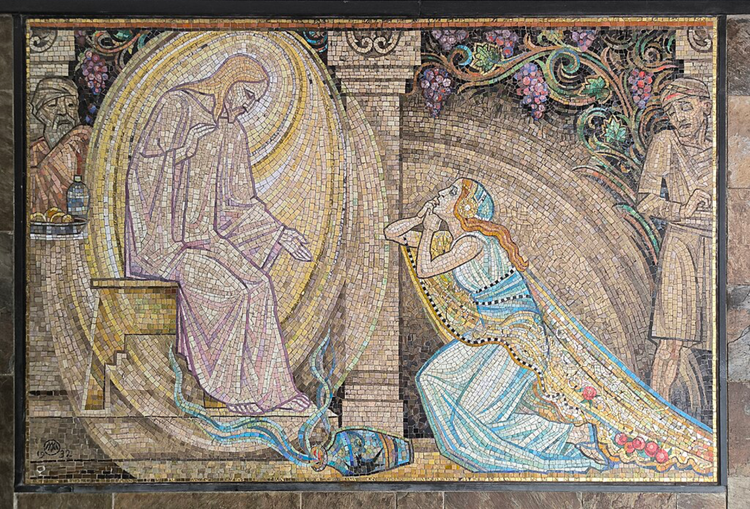

I. What If Sin Isn’t What You Thought It Was?

When Peter asks Jesus, “What is the sin of the world?” the answer comes as a shock:

“There is no such thing as sin. You only make it appear when you act according to the habits of your adulterated nature.”

— Gospel of Mary, §7 (David Curtis translation)

It’s not that wrongdoing doesn’t exist. It’s that what we’ve called “sin” is actually a form of forgetting — of misalignment, distortion, or self-betrayal. Not an inherited stain, but a mistaken identity.

“Suffering arises because it goes against your true nature.”

We begin life whole — and then the world happens. We take on layers: grief, addictions, despair. Some wear shame like a second skin. Others, depression like a leaden cloak. A friend of one of the women in our circle once said, “I wish I could just peel my skin off — to get rid of all the stuff that’s not me.”

“It’s like watching a beautiful, innocent baby grow up into a surly teen,” someone else said. “They begin so pure, but fifteen years later they think their only worth is what they have, how popular they are, and who they know.”

And a lot of people never outgrow the “have, have not, and want” mindset.

That’s what this gospel is about.

II. The Child of Your True Humanity

Jesus tells the disciples:

“Be vigilant, and don’t let anyone lead you astray by saying ‘Here it is’ or ‘There it is,’ for the Child of Your True Humanity already lives within each one of you.”

This isn’t just about where to look for God. It’s about what you are, and what you’ve forgotten.

The phrase — “Child of Your True Humanity” — sounds mystical, but it’s remarkably grounded. You might read it as “Christ consciousness,” or perhaps the original soul-spark within. The idea that your deepest identity is already aligned with God — not in need of punishment, but in need of remembrance — is echoed across mystical Christianity.

- The desert monks called this clarity the nous: the purified, undistorted eye of the heart.

- The Gospel of Thomas says, “When you come to know yourselves, then you will be known.”

- And Luke 17:21 has Jesus declaring: “The kingdom of God is within you.”

Even the worst among us, Jesus suggests, still carry that glimmer of original light — obscured, but not extinguished.

III. Original Sin: A Theological Rebuttal from the Gospel of Mary

The doctrine of “original sin” — that humans are born fundamentally broken — didn’t appear until the 2nd century. Irenaeus, a bishop in Gaul, introduced it as a rebuttal to the Gnostics. It was later codified by Augustine (around the turn of the 5th century) and calcified into Western theology.

But in the Gospel of Mary — a text likely circulating in the mid-2nd century — we find a radically different view:

“This is what sickens and destroys you: your love for the things that deceive you.”

Not your nature. Not your birth. Not your body.

But your attachment to illusions — to things that aren’t, at a fundamental level, even real.

You’re not damned from the start. You’re divine — and distracted.

Evagrius Ponticus, the 4th-century desert monk, would have nodded in agreement. He taught that sin was not a legal transgression, but a distortion of the heart’s vision. The spiritual path was not one of guilt, but of clarity.

IV. This Gospel Still Speaks

One of the women in our circle said it best:

“It felt like something I already knew, but didn’t have the words for.”

That, I realized, is what spiritual awakening often feels like — not discovering something new, but recovering something you’ve always known. Something that had been buried beneath wounds, roles, ambitions, doctrines, or shame.

We’re not so much becoming holy as remembering that we already are.

Questions for You

- What false selves have you picked up over the years?

- When do you most feel in alignment with your true humanity?

- What would it mean to believe that the kingdom of God is not far away — but already within you?

Sources & Citations

- David Curtis, The Gospel of Mary (Third Draft), thegospelofmary.org

- Wiley, Tatha. Original Sin: Origins, Developments, Contemporary Meanings. Paulist Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-8091-4128-9 Available at Bookshop.org, Alibris, and Amazon.

- Gospel of Thomas, Saying 3 — The Gnostic Society Library.

- Luke 17:20–21

- Evagrius Ponticus, Praktikos and Chapters on Prayer

Want more?

This is part of an ongoing series on early Christian mysticism, forgotten gospels, and soul-deep spirituality.

If this essay stirred something in you — if you're drawn to the quiet, mystical voices of early Christianity, or if you’re seeking a faith that leads you inward, not into fear — consider subscribing.

Every week, I explore faith, mysticism, and memory at the crossroads of history and the heart.

You’re warmly invited.

This was originally published as The Gospel of Mary and the Child of Your True Humanity