When Yahweh Had a Bull’s Head

What Ancient Israelite Art Reveals About God, Asherah, and Early Hebrew Spirituality

Many people today follow the laws of the early Hebrew Bible as if they were timeless mandates yet these laws emerged from a worldview whose symbols, metaphors, and religious imagination were profoundly different from our own.

We often miss this because when we picture Abraham, Moses, and Yahweh, we rely on images inherited from Renaissance art rather than ancient Israelite culture.

But those images reflect a later European theology — not the mental world that originally produced the texts.

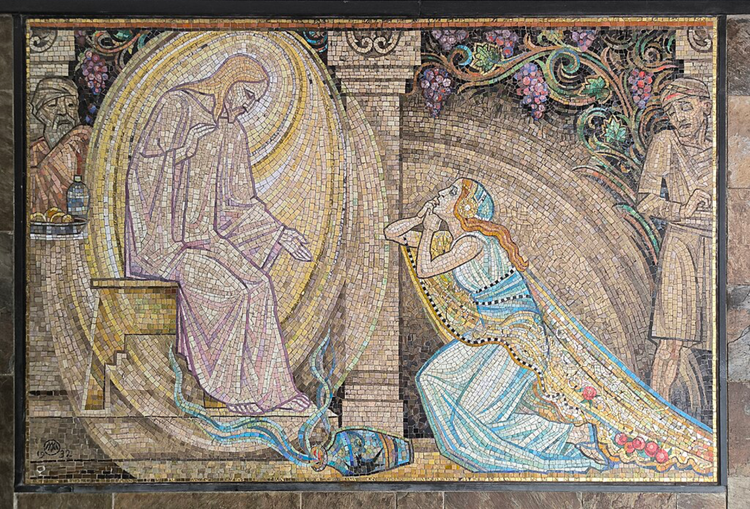

How Renaissance Artists Rebranded Yahweh

The illustrations above fit pretty closely to the mental image most of us have when we think of Yahweh / God — even those who acknowledge, intellectually, that it’s a metaphor.

Images like these have shaped widespread misconceptions that Christianity is European — or even American — in origin.

What then are we to think when we see how the ancient Israelites actually envisioned their God?

Let’s take a look.

Cave Paintings, or Ancient Hebrew Religious Art?

If you’re thinking the illustration above looks like rock paintings from Lascaux, Namibia, Kakadu, or the lower Pecos, you may be surprised to learn its true origin — a ceremonial jar excavated from an Israelite worship center in the eastern Sinai Peninsula.

Sinai pottery like this dates to the Early Iron Age 1200–600 B.C.E., an era that corresponds to the early kings — Saul (reigned 1021–1000 BCE), David (1000 to 962 BCE), and Solomon (962–922 BCE), found in 1st Samuel. Prophets Elisha, Jonah, and Joel were active around the year 800 B.C.E.

The inscription identifies Yahweh and “his Asherah,” so it’s pretty clear whom the artist intended to represent.

The careful observer will see that Yahweh has the head of a bull, topped by a large crown. His anatomy is overtly emphasized, underscoring themes of fertility and virility in ancient symbolism.

Asherah, beside him, has the head of a cow, a crown, and round breasts.

The image of a mother cow lovingly cleaning her a suckling calf to the left of the pair points up the traditional symbolic connection between Yahweh / Asherah and cattle.

The ancient Hebrew artist also reveals to us the relationship between this divine pair and their followers; they provide life, care, sustenance, and protection for devotees, just as a bull and cow create, protect, and nurture a calf.

Potent & Symbolic: This Works For Me

Now, I find this representation of God surprisingly compelling. After nearly 3,000 years, thinking of Yahweh this way seems fresh.

The symbolism is potent.

And yet, it’s not surprising if we look at the cultural stew from which ancient Hebrew religion emerged — the Apis bull of Egypt, as well as bulls representing deity in Mesopotamia, Minoan Crete, Roman Mithraism, and Canaanite religion (the Bull El).

Even the infamous Golden Calf episode in Exodus 32 shows how bull / cow / calf imagery was once part of El and later Yahweh worship before the Levites slaughtered the participants.

Recognizing these symbols — Yahweh as bull, Asherah as cow — invites us to see the ancient Israelites’ concept of God as embodied and intertwined with the rhythms of their world. They embodied fertility, abundance, and protection, but one needed to remain respectful.

By depicting Yahweh and his Asherah as cow-headed deities, ancient Hebrew artists tried to show us, even today, that the divine shared those characteristics.

Reflecting on the fact that these texts emerged from a culture both far more rustic and symbolically rich than our own broadens and informs my own spirituality.

Takeaway Questions

Take a moment to reflect on the images received from Western art since the Renaissance. Then take another glance at the art above — created in same the era as the books of 1 & 2 Samuel, 1 & 2 Kings, and 1 & 2 Chronicles in the Hebrew Bible.

- How does that challenge or change our mental images?

- Which one is more powerful to you — later, Renaissance-era image of a distant, paternal deity floating majestically in the clouds, or the earnest, primitive imagery?

- Does your answer change deepening on the situation?

- How do these insights challenge us regarding the rules and narratives handed down from the early Hebrew texts?

Why This Matters Now

The God we picture shapes the faith we practice.

If we continue to imagine Yahweh only as a cloud-dwelling patriarch with a flowing beard — styled by Renaissance artists rather than ancient prophets — we risk mistaking someone else’s metaphor for eternal truth.

But when we recover the raw, rooted imagery of early Hebrew spirituality — like the cow-headed Asherah and bull-crowned Yahweh — we remember that the divine was once understood through fertility, embodiment, and relationship with land and animal.

And thank God, it can’t be used by Christian Nationalists; it’s not about empire, control, or whiteness.

Let’s not approach this as a simple historical curiosity. It’s an invitation:

- To decolonize our theology.

- To unfreeze our imagination.

- To find God not in the image handed to us, but in the ones we, as a culture, have forgotten.

I find this all heartily inspiring.

My own spiritual life is renewed by this experience of God outside the strictures of hidebound imagery.

I hope it’s done the same for you. Blessings.

For more, check out other pieces in this series: