Creole Religion: How Ancient Gods Shaped Christianity and Judaism

On shared spiritual ancestry and the myth of divine purity

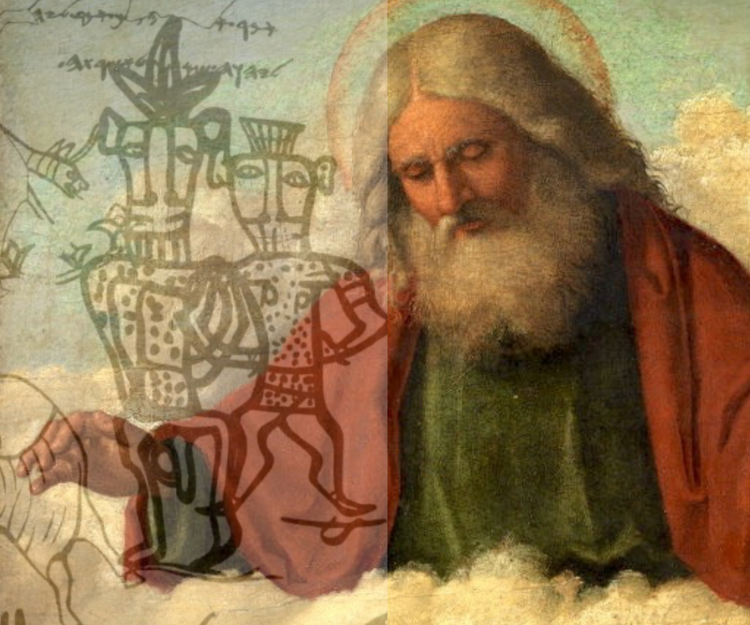

Baal shouldn’t be wearing an Egyptian crown.

Yet this Late Bronze Age figurine from Megiddo shows the Canaanite storm god dressed in the hedjet — the tall white crown of Upper Egypt. His raised fist once gripped a javelin. His stance is unmistakably martial: part warrior, part sky-god, part political statement carved in bronze.

Why would a Canaanite storm god dress like a pharaoh?

Because ancient gods didn’t stay in their lanes.

Long before monotheism, religion traveled the way people did: along trade routes, through diplomatic marriages, in the luggage of merchants, with soldiers marching north or south, across dusty border checkpoints where Egypt met the Levant. When cultures intersected, their theologies didn’t simply blend — they recomposed themselves.

If you lived in Megiddo around 1300 BCE, you would have known Egyptian officials, Canaanite scribes, migrant laborers from Syria, and traders from Cyprus. You could hear several languages in a single market. And in a city like that, your gods inevitably rubbed shoulders with other gods.

When Empires Shape Theology

Egypt’s involvement in Canaan wasn’t sporadic, subtle or symbolic. It was structural, and administrative. We have letters from Canaanite rulers begging Pharaoh for military protection, complaining about local rebellions, and reporting grain shipments down to the last basket. Egyptian commissioners were stationed in key cities to oversee taxes, trade, and temple resources. Egyptian scribal training shaped the bureaucrats of Canaanite city-states, and Egyptian religious festivals were sometimes observed alongside local ones. When you looked up from your everyday life in a place like Megiddo, you saw Egyptian architecture, Egyptian officials, Egyptian soldiers, and Egyptian ritual objects.

In such an environment, it makes perfect sense that religious imagery followed the same lines of influence. If the empire governed your crops, your trade routes, and your political alliances, it naturally governed your imagination of the divine. A god who could wear the crown of Egypt was a god who understood how power worked in a world shaped by empire.

For nearly 300 years, Egypt exerted political and economic control over much of the Levant, sometimes directly and sometimes through local vassals. Egyptian garrisons were posted in Canaanite cities. Egyptian administrators collected grain taxes and appointed mayors loyal to Pharaoh. Egyptian iconography appeared on everything from jewelry to pottery.

For nearly 300 years, Egypt exerted political and economic control over much of the Levant, sometimes directly and sometimes through local vassals. Egyptian garrisons were posted in Canaanite cities. Egyptian administrators collected grain taxes and appointed mayors loyal to Pharaoh. Egyptian iconography appeared on everything from jewelry to pottery.

In a world where power was theological, Egyptian symbolism carried cosmic weight.

If Pharaoh ruled Canaan, then Pharaoh’s gods ruled the cosmic order surrounding Canaan. And if your local god — Baal, Resheph, Astarte — wanted to be seen as powerful in this shifting political landscape, borrowing the crown or attributes of an Egyptian deity was no small thing.

It was a claim on legitimacy.

A way of saying:

Our god speaks the language of empire too.

Our god stands among the powerful.

In a time before strict doctrinal boundaries, this wasn’t controversial — it was normal. Religion adapted to politics. Deities acquired new symbols the way kings acquired new titles.

The Divine Feminine Never Stayed Put

The same is true for goddesses, often even more so.

Asherah — central to the pantheon of early Israel and long suppressed in later biblical memory — absorbed characteristics from neighboring goddesses like Hathor, Astarte, and Anat. The Hathor wig in particular appears in several Levantine depictions of female divinity: long, curled braids framed by a wide headpiece that unmistakably signals Egypt.

The Hathor wig also carried ritual and social meanings that transferred easily into Levantine life. Hathor was the patroness of musicians, midwives, dancers, and women who mediated between the domestic and the divine. Her imagery represented joy, fertility, erotic power, and cosmic motherhood. When this iconography enters Canaanite art, it often appears in domestic shrines — small clay plaques, household figurines, and cultic objects used by families rather than temples. This tells us something important: women were key agents of religious transmission. They shared stories, traded amulets, adopted healing rituals, and preserved traditions across borders. When Asherah carries Hathor’s features, it shows us not just theological merging but the lived religious reality of women whose spiritual instincts crossed borders long before male scribes tried to regulate the divine.

Hathor was a goddess of motherhood, joy, beauty, sexuality, and divine protection. When her imagery crossed into Canaan, it wasn’t merely copied — it was translated. Asherah, already the mother of the gods and the embodiment of sacred nurture, could wear the Hathor wig without losing her identity. She didn’t become Hathor; she absorbed her. She expanded.

Hathor was a goddess of motherhood, joy, beauty, sexuality, and divine protection. When her imagery crossed into Canaan, it wasn’t merely copied — it was translated. Asherah, already the mother of the gods and the embodiment of sacred nurture, could wear the Hathor wig without losing her identity. She didn’t become Hathor; she absorbed her. She expanded.

This fluidity wasn’t theological chaos. It reflected people’s real experiences. Women traded across borders. Families intermarried. Midwives migrated. Healers traveled. Goddess traditions crossed with them.

If you were a mother in the ancient world, you didn’t care whether your protective goddess was technically Canaanite or Egyptian — you cared whether she showed up.

The Qetesh Plaque and the Art of Blended Divinity

One of the most vivid examples of this blending is the Qetesh plaque — a relief showing three goddesses from three cultural zones standing side by side: Qetesh, Astarte, and Anat. Egyptian, Levantine, Syrian. All distinct. All merged.

This isn’t evidence of religious confusion.

It’s evidence of religious competence.

To the ancient imagination, divine power was additive. Gods could coexist without contradiction, merge without violence, and share functions without needing to defend doctrinal turf.

The idea that religion must be internally airtight, consistent, and singular is a modern bias. Ancient people never required such rigidity. Gods were powerful because they were adaptable.

This adaptability is the soil — rich, mixed, border-crossed — from which both Judaism and Christianity grew.

The Myth of Pure Religion

This brings us to an uncomfortable but necessary truth:

Neither Christianity nor Judaism descended from a single pure revelation.

They emerged from the same spiritually entangled world in which Baal wore an Egyptian crown and Asherah donned a Hathor wig. Their earliest traditions grew out of:

- Mesopotamian cosmology (creation stories, flood narratives, divine council imagery)

- Canaanite religion (El, Baal, Asherah, the high god and his council)

- Egyptian symbolism (solar imagery, royal iconography, goddess traditions)

- Persian theology (angels, resurrection, dualism)

- Greek philosophy (soul-language, virtue, metaphysics)

- Roman political theology (empire as divine order, law as sacred)

The editors who eventually shaped the Hebrew Bible fought hard to present a unified story, sometimes condemning foreign gods with fierce rhetorical fire. But the archaeological layers don’t lie. The cultural memory doesn’t lie. The inscriptions and figurines and borrowed crowns don’t lie.

Religious mixing wasn’t the exception.

It was the starting point.

And even the attempts to suppress syncretism are evidence that it existed — and thrived.

The Blending Didn’t Stop in Antiquity

Syncretism continued long after the biblical writers put down their pens.

- Early Christianity borrowed liberally from Greek philosophical vocabulary.

- Jewish mysticism absorbed strands of Neoplatonic cosmology.

- European Christianity blended saints with local deities and ancestral traditions.

- African and Caribbean Christianity became creole in the truest sense — braiding together Catholicism, indigenous religion, and African cosmology into something spiritually alive and enduring.

- Modern Christianity quietly retains pagan festivals, seasonal rituals, and folk practices woven into its liturgical calendar.

Every attempt to enforce theological purity — ancient or modern — has failed.

And for good reason:

Purity is brittle. Syncretism is resilient.

A religion survives not by sealing itself off, but by absorbing and reinterpreting the world around it.

Why This Matters for Us Today

We live now in another age of border-crossings:

- migration

- digital diaspora

- interfaith families

- global culture

- instantaneous communication

- spiritual communities without geographic boundaries

In such a world, it’s worth remembering that our ancestors practiced creole religion long before we had words for it. And the faiths that endure — Judaism, Christianity, and others — endure precisely because they adapted.

When people insist today on “pure faith,” “correct doctrine,” or “returning to the original,” they’re not defending tradition. They’re defending a myth.

Real tradition is porous.

Real faith is flexible.

Real theology evolves.

You can see that evolution in every archaeological stratum — from the Bronze Age temples of Ugarit to the Iron Age shrine inscriptions that name “Yahweh and His Asherah,” to the syncretic Christianities that emerged across Africa, Asia, the Caribbean, Europe, and the Americas.

Most of the loudest voices insisting on “pure” Christianity or “original” Judaism are unaware that such purity never existed. What they’re claiming to defend is an imaginary past — one where religion stood unchanging and untouched by the world around it. But the archaeological record shows something far more interesting and far more hopeful: religions are strongest when they adapt. They become more compassionate, more intellectually resilient, and more spiritually spacious when they acknowledge their own layered history. In a pluralistic world where people marry across traditions, practice hybrid spiritualities, and live in digital borderlands, understanding that ancient faiths were also hybrid can liberate us from the anxiety of getting everything “right.” Faith doesn’t need to be pure to be powerful. It needs to be alive.

The story is always the same:

Faith survives because it blends.

The Borderlands Are Where Theology Comes Alive

Theologies don’t emerge from isolation.

They emerge from contact — messy, creative, unpredictable contact.

Ancient Megiddo was a borderland city. So was Ugarit. So were Elephantine, Byblos, and Jerusalem. The same can be said of Alexandria, Antioch, Rome, and later the Mediterranean ports where Jews, Christians, and pagans debated, influenced, borrowed, and reshaped each other.

The borderlands are where gods changed clothes.

Where theologies met.

Where religions grew.

And they still are.

When we look honestly at the archaeological record, we see not religious decline or corruption, but religious imagination — a bold willingness to adapt divine imagery to new realities.

That’s not something to fear.

It’s something to learn from.

If this resonates…

Be sure to check out other pieces in this series:

- When Yahweh Had a Bull's Head

- The Men Who Silenced Asherah Still Silence Women Today

- How Yahweh Became God: From Canaanite Deity to World Religion

These pieces explore different facets of the same truth: that religion has always been creole, and that this is precisely why it has endured.

(Original version, begins here.)

What’s Baal doing in an Egyptian crown?

This bronze figurine — found in ancient Megiddo — shows the Canaanite storm god Baal wearing a crown likely inspired by the Egyptian white crown (hedjet) of Upper Egypt.

Why would a Levantine god dress like a pharaoh?

Because the gods of the ancient Near East didn’t stay in their lanes.

Egyptian and Canaanite cultures interacted constantly — through trade, war, migration, and intermarriage. And just like people, their gods borrowed from one another.

Sometimes a crown wasn’t just a crown — it was a symbol of legitimacy, of cosmic power, of empire. If Egypt was dominant, then dressing Baal like an Egyptian god might make him more powerful, more cosmically plugged-in.

In Egypt, this kind of divine blending was common. Syro-Levantine goddesses like Qetesh (also called Qadesh or Qudshu) were depicted with Hathor-style hair and headdress, standing on a lion and flanked by Egyptian and Canaanite gods alike. Her very image is a theological merger — Canaanite fertility goddess, Egyptian iconography, shared divine functions. The gods crossed borders in wigs, crowns, and symbols.

Religions evolve by borrowing.

Every faith is creole. No god was ever an island.

This is the uncomfortable truth I hope to explore in this series: the idea that Christianity — or Judaism — descends seamlessly from a single divine revelation is a comforting illusion.

In reality, both traditions have been shaped and reshaped over millennia, absorbing elements from Mesopotamian, Levantine, North African, Greco-Roman, and European religious traditions.

The editors and priests who compiled their scriptures tried to smooth over contradictions, to make everything fit — but the history of these faiths is anything but pure or consistent.

Even the Bible itself preserves traces of this older, messier world. Psalms use the language of ancient storm-god hymns. In Deuteronomy 32:8, some of the earliest manuscripts describe God dividing the nations among the “sons of God” — a divine council — while later versions replace this with “sons of Israel,” softening the polytheistic implication. Later editors quietly adjust the language, smoothing divine multiplicity into monotheistic theology.

And the process never stopped.

Religions are living systems. They grow by absorbing, reinterpreting, and transforming what came before them. So anyone who beats the drum about theological purity, orthodoxy, or orthopraxy is usually defending an invented past that never actually existed.

Accepting religious exchange and merger is not a modern heresy, cooked up by New Age influencers and progressive Christians — it’s theology’s birthplace. Because all living things grow and change, it’s also theology’s future.

In our age of global contact, interfaith families, and digital religion, this ancient pattern is accelerating again. The future of faith won’t be about defending old boundaries; rather, it will be about learning how to live inside religious commingling without fear.

To learn more, check out the other pieces in this series: